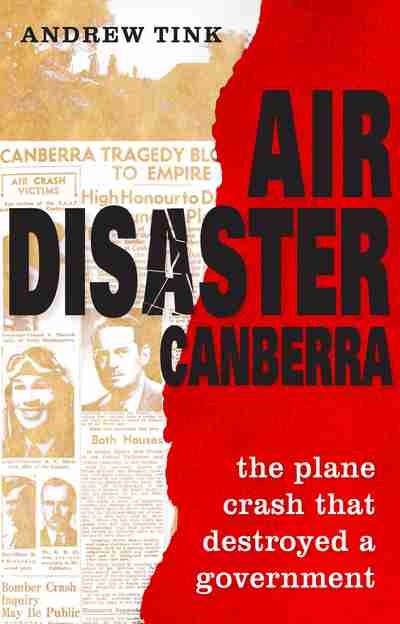

Andrew Tink: Air Disaster Canberra. The Plane Crash that Destroyed a Government (ADF Journal)

Air Disaster Canberra is divided into three sections, the political rise of the Anzac generation; the last flight of Hudson A16-97 on 13 August 1940; and an account of the destabilisation and destruction of Menzies government which led to John Curtin’s prime ministership in October 1941.

This is Andrew Tink’s third book; his first, William Charles Wentworth: Australia’s greatest native son, won ‘The Nib’ CAL Waverley Award for Literature and his gift for narrative is again apparent. A former member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Andrew Tink’s parliamentary experience is evident as he expertly argues the political ramifications of the crash. I was particularly impressed by the word portraits of the ten men who died. He also brings his descriptive talents to those who appear briefly such as Jack Lang of the ‘rasping voice, snarling mouth

and flailing hands when he spoke ... [and] lower jaw like a steam shovel blade’, and Charles Hawker whose ‘limping gait and glass eye were powerful reminders of wartime sacrifice’.

Air Disaster Canberra touches on some significant side issues including the apparent mishandling of the evidence at the crash scene—careful treatment of the human remains would have left no doubt as to who was the pilot—and the foolhardiness of allowing so many key personnel to travel together. At its heart, however, are two arguments: that the crash of Hudson A16-97 and the deaths of all on board led directly to the change of government the following year, and that Jim Fairbairn had been at the controls.

Fairbairn was a skilled pilot who had served with the Royal Flying Corps during the Great War. He had flown many different types of aircraft and brought a depth of personal flying experience and administrative ability and innovation to his ministerial portfolios. He believed his work would benefit from his knowledge of every aspect of aviation and so he wanted to fly as many different types of aircraft as possible, including the Hudson.

For the main part, Andrew Tink has assembled solid evidence to support his speculation about Fairbairn. I feel, however, that that of Herb Plenty, a fellow pilot of Bob Hitchcock who became a senior peace time air force officer, is less sound. Plenty claimed almost 70 years later that Hitchcock’s squadron leader had orally condoned Hitchcock allowing Fairbairn to have ‘a touch of the controls’. This information had been intimated to Plenty by the squadron leader at a post war social function. Plenty’s hearsay testimony aside, Andrew Tink considers many other factors which better support his argument.

For many years, Bob Hitchcock’s flying ability has been called into question, most notably by former RAAF Historian Chris Coulthard-Clark, in The Third Brother and Hitchcock’s near contemporaries, Richard Kingsland and Herb Plenty. In arguing that Fairbairn was at the controls, Andrew Tink provides evidence attesting to Hitchcock’s skill with the Hudson and number of incident-free hours flown in this type. I was very pleased to see this reappraisal of Hitchcok’s airmanship, after all many fine pilots took time to develop their skills. Pat Hughes, for instance, who was a year behind Hitchcock at Point Cook, was ranked 28th in his course and assessed as having no outstanding qualities.

Andrew Tink claims that it was reasonable for Fairbairn to take the risk of landing the Hudson and that he deserves his place in history as a respected ‘aviation hero, whose pioneering work, both before and during the war, helped to make flying safer for everyone’. I agree, but I am not comfortable that Andrew Tink fails to acknowledge that, if Fairbairn was at the controls, he was responsible for the deaths of nine men as well as his own. To me, Fairbairn’s hubris in believing he could do what RAAF pilots had to be properly trained to do and his selfishness in putting his own desires ahead of the safety of those nine men equates to Richard Hillary’s selfishness in wanting to fly again despite fire-mutilated hands that could, apparently, barely hold a knife and fork, with the ultimate consequence of his own death, and that of his radio-operator/navigator.

I might not agree with every aspect of his argument, but I was fascinated by Andrew Tink’s account of the demise of Hudson A16-97 and all on board. Ultimately, I was swayed by his reasoned speculation. I was entranced by his careful analysis of the consequences of the loss of three cabinet ministers. I firmly agree with his disappointment in the current state of Canberra’s memorial to the crash victims. But where Canberra fails to honour, Andrew Tink does not. He is to be congratulated for writing not only their tribute but in placing their death in a broader political context. Highly recommended.