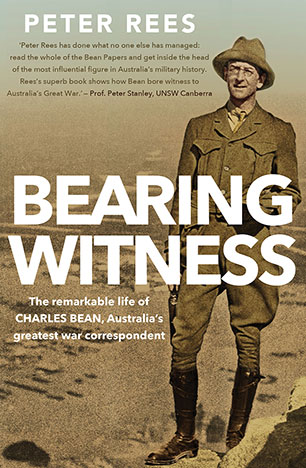

Bearing Witness. The remarkable life of Charles Bean, Australia's greatest war correspondent.

Peter Rees. Allen & Unwin: Sydney, 2015. Appeared in online edition of Issue No. 197, July-August 2015 of the ADF Journal.

Charles Edwin Woodrow (CEW) Bean, the man who wrote six of the volumes of Australia’s Official History of the War of 1914–1918 and edited the other six, left a significant archive of writings. That archive, however, is so substantial that the casual enquirer could not hope to master even a small portion of it. Peter Rees has delved into the monumental accumulation of records (including 226 volumes of diaries) and mastered it to such an extent that in Bearing Witness: the remarkable life of Charles Bean, Australia’s greatest war correspondent he is able to get inside his subject’s head.

Not only that, Rees, whose career path mirrors Bean’s in many ways—he too moved from journalist to history writer—was able to draw on his own considerable experience to explain and interpret Bean’s. The result is that the reader feels as if he or she knows the subject intimately in this deeply-researched, well-written and utterly accessible biography.

With so much primary source material relating to Bean’s work as a war correspondent and official historian, the temptation would be to focus on that period of his life. It is testament to Rees and his publisher that they agreed not to curtail a discussion of Bean’s formative years because in this section the reader discovers the basis of Bean’s moral code which informs his writing practice and commitment to accurately bear witness. ‘Be truthful’, Bean’s mother exhorted the six-year old boy. Be ‘morally brave’. Be a ‘good, charitable man’. By describing the world of Bean’s childhood and youth, his family and influences, and his early accomplishments, the reader clearly sees Bean’s maturing intellectual honesty, his morality and his dogged pursuit of truthful reportage.

The trajectory of Bean’s career as war correspondent and historian is well known. There is no need to discuss it here. What perhaps is less known is the development of the personal philosophies which underpin his writings, especially the Official History. Rees discusses Bean’s perception of mateship, nationhood, and belief in the goodness of his fellow man. We discover how reporting the Great War, at the same time as gathering material for the future task of writing the official history, created conflicts with the military censors and even his own writing practice.

For instance, criticism was relegated to his war diaries/notebooks (‘it made you mad to think of the dull, stupid, cruel bungling that was mismanaging the medical arrangements’, for example) and the ‘bright side’ of the war was the foundation of his published newspaper despatches, which he referred to as ‘letters’. Taking only the diaries or despatches as source documents, Bean realised, would lead to a skewed appreciation of his war. ‘If ever it [his diary] were used it would have to be used most carefully.… I can’t write everything here as well as in my letters’. A useful warning to any historian: look at the entire body of evidence, rather than sources in isolation.

Bean may have edited the criticisms from his despatches and bowed to the strictures of censorship but Rees was not tempted to brush over the negative aspects of the war correspondent’s character. Late at night on 25 April 1915, a day that started well before dawn and saw the death of 101 men in the first wave of landings alone, the reader catches a rare glimpse of an insensitive Bean. Noisily constructing his own dugout, he bridled at the complaint of a neighbour, a no doubt exhausted signaller, who could not sleep from the racket Bean was making.

Rees also shows us that, on occasion, Bean failed to live up to his mother’s plea to be morally brave. After a raid in June 1916, where members of the 7th Brigade captured soldiers from a Prussian infantry regiment, Bean recorded that the Australians and their prisoners were caught in shellfire. One of the panicked Prussians struggled and could not be subdued. The Australians cut his throat. Two more prisoners ‘did not seem to understand what was required of them—at any rate they didn’t do instantly what was required of them—and were shot on the spot’. We can well understand why Bean the reporter would not include this incident (a potential war crime?) in the subsequent despatch home but should not Bean the historian have included it in the official history?

For the most part, however, Bean was morally brave in his reporting, struggles with the military, and history writing. Rees is also morally brave because it takes courage to portray all sides of a man who has long been lauded. Lucy Bean would have been just as proud of Rees and this warts-and-all, vices and virtues biography, as she was of her son.

If you want a history of the Gallipoli campaign or the battles on the Western Front, this book is not for you. If you want to discover more of the man who reported those battles and constructed the first detailed history of them, you could do no better than to read Bearing Witness. It is a well-rounded, revealing biography of Bean the man, reporter, historian and passionate advocate of Australian nationhood. Recommended.