Leon Kane-Maguire: Lost Without Trace. Squadron Leader Wilbur Wackett, RAAF. A Story of Bravery & Tragedy in the Pacific War

The biennial RAAF Heritage Awards were established in 1987 to foster an interest in the history of service aviation and enhance RAAF records. Awards are given for outstanding achievements in literature and art, and assistance is given to those undertaking historical research. As well as a generous prize, the literary award includes publication of the winning manuscript. These memoirs, biographies and historical accounts have added considerably to Australian air force knowledge. Lost Without Trace, which won the 2010 award, is a welcome addition to the RAAF’s publication program.

Leon Kane-Maguire was one of Australia’s most respected scientists and, as well as over 175 scientific papers, he had written or co-written three RAAF squadron histories. He died in January 2011 and never saw his final work in print.

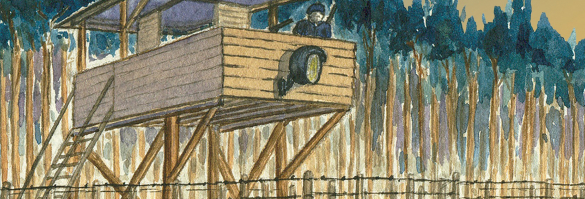

Lost Without Trace is a biography of Wilbur Wackett, son of Lawrence Wackett, who flew in the Australian Flying Corps during the Great War and founded the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation. Wilbur followed his father’s footsteps into the air force and served with 2, 24, 75 and 31 squadrons. With 75 Squadron, he participated in the New Guinea air campaign during which he was shot down. Barefooted, he spent a month crossing Papua’s rugged terrain, avoiding capture, to return to his comrades at Port Moresby. In September 1944, 23 year-old Wilbur’s Beaufighter crashed in the Northern Territory. Evidence was later discovered that Wilbur and his navigator had survived, but there was no sign of what had become of them. The bulk of this biography deals with Wilbur’s background, training and RAAF service but the heart is his loss in September 1944 and the aftermath.

I enjoyed Lost Without Trace but I have one concern and one criticism which I will get out of the way so I can give the praise it deserves. Firstly, heritage manuscripts are supposed to be 55,000 words, although longer manuscripts may be considered. Lost Without Trace is just under 60,000 words (including standard preliminaries). With such a tight word limit an author must make hard decisions about what to include and what to omit; the ruling doctrine must be ‘if it does not specifically relate to the central subject, leave it out’. My concern is that Kane-Maguire did not make the best use of his word limit when he included large extracts from non-Wilbur material. For example, blocks of scene-setting recollections should have been pared to a few descriptive sentences, and a handful of survey paragraphs would have served better than the pages describing the fall of Rabaul when Wilbur—a recent posting to 24 Squadron—was in Townsville. My sole criticism is no fault of the author: it is the lack of an index. I believe an index is essential for any historical work.

And now to the praise. Kane-Maguire’s literary talents are obvious in Lost Without Trace. He had the support of Wilbur’s extended family and competently drew on their archives and other available source material. The text is well-written and sparkles with Wilbur’s letters and diary extracts. His whimsical sketches are a charming and enlightening addition. It is a shame Wilbur did not write more as there are large gaps in his diaries but they are largely filled by drawing on recollections and the historical record.

The danger in quoting letters in their entirety, as Kane-Maguire has done, is that the incidental can distract from the important. Where few contemporary witnesses remain, however, they become an essential gauge of personality and character. In including Wilbur’s letters almost unedited, Kane-Maguire has allowed Wilbur’s personality to shine through. His enthusiasm for his flying and RAAF work is vivid and I for one was glad to read of the exciting and mundane in his service career. Perhaps Wilbur’s account of his difficult trek across Papua could have been shortened but, penned shortly after his return to Australia, it is a significant document and through it the reader gains a clear impression of the hardship Wilbur—and other evaders, for that matter—endured during the long and dangerous walk home through Japanese territory.

I always find ‘last letters’ moving. With the benefit of hindsight, I cannot keep the knowledge of what-happens-next from my reading of them. And so it is with Wilbur’s. It is to his parents, and, as he congratulates them on their silver anniversary, he shows clearly the depth of his love for his young bride. He touches on the pride and love for his daughter who he will never see, and we feel his stoic sadness that he is missing out on her growing up. His joy in flying is briefly encapsulated when he proudly declares that ‘I have my own kite now and she’s a little honey.’ The final poignant request—‘do not worry about me I’ll be OK, and home again before you know where you are’—is heart wrenching. This is one letter that needed to be published in full.

Wilbur’s story resonates. He never returned home. His body was never found. We share the Wacketts’ pain, their frustration at the dearth of official information, Lawrence Wackett’s desperate attempts at string-pulling to find out more, and the ultimate despair of not knowing what happened. We grieve at the continuing loss for the Wackett family: the deaths of Wilbur’s daughter when she was only fourteen months old and his wife, Peggie, at a young age.

The Wackett family only learned in 1980, by chance, that Wilbur had survived the crash and Peggie, who died in 1956, never knew. We wonder at how vital grief-assuaging information and relics were not passed on when first discovered. In piecing together what happened to Wilbur after his September 1944 combat, Kane-Maguire has provided closure for Julie, Peggie’s daughter from her second marriage, and Wilbur’s extended family.

Leon Kane-Maguire’s posthumous literary gift is a fine biography and a fitting memorial to Wilbur.