Mike Hayes: Angry Skies. Recollections of Australian Combat Fliers

Right at the beginning of this book, the publisher noted that every attempt had been made to ensure that names, dates and facts are correct. Sadly, this was not the case. I was annoyed by the mistakes. Not only typos, but errors of fact. I will admit I am a military history novice, and I bow to the superior knowledge of my colleagues, so it really makes me worry when I pick up errors!

Other things also annoyed me about this book. Firstly, the fact that the book is subtitled ‘Recollections of Australian Combat Fliers’ when two of those interviewed, the WWI representatives, were not pilots. Although their stories were interesting, Hayes had to work hard to justify their inclusion. Secondly, Hayes’ belaboured attempt to prove a link between the fictional adventures of Biggles and the reasons why some of the pilots joined the air force. Thirdly, the changes between style: shortish extracts arranged around themes, some tenuously illustrated, and long extracts where the pilots were given free reign to speak of their experiences. (Perhaps this aspect might have been sorted out in the normal process of authorial editing had not Hayes passed away suddenly earlier this year.) Fourthly, that in many instances, the interviewees’ stories were cut off when they became interesting, or pulled apart to illustrate a point. Finally, the lack of an index.

Twenty-four interviews with airmen, conducted by Wing Commander Ken Llewelyn, from WWI through to the present day were drawn on in varying degrees. Hayes explored the reasons for flying (the dreaded Biggles factor mentioned above); training experiences; the types of planes flown, fighters, bombers, flying boats; and the differences between WWII combat and later twentieth century techniques. I loved reading about the interviewee’s experiences, but the annoyances did intrude on my enjoyment: Black Jack Walker and Stuart Cameron might as well have been left out given they were mentioned only briefly; and entertaining accounts such as Marcel Dekyvere’s were rearranged and used to illustrated a number of different themes.

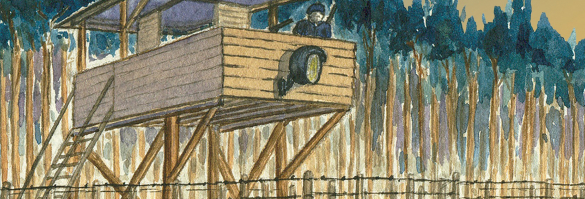

For me, the main strength of this book was when the interviewee’s story was uninterrupted, such as in Ron Guthrie’s chapter-length description of his final mission, capture, escape and recapture, and time as a POW of the North Koreans; the longer descriptions of bombing missions by Jack Davenport and Peter Coldham; and Tony Burcher’s description of his dambusting mission and later capture by the Germans. These segments had it all: action, fear, suspense, and were told by natural storytellers.

At the Canberra launch of this book, Ken Llewelyn commented that as the WWII aircrew grew older, the tall tales that regaled the eager listener at long, boozy lunches often turned to more honest accounts. This honesty shone through here clearly. The fear that the young pilots experienced in the face of danger; Bobby Gibbes’ admission that he felt apprehensive and ‘made a bit of a goat of myself’ on his first combat mission; Lionel Rackley who admitted that his flight commander was a ‘thorough bastard’; Marcel Dekyvere who wasn’t coy about his social life, ‘Come off it. Of course, we all had girlfriends….I had one in every port’ (particularly brave and honest when I recollect that he was married only shortly before leaving for overseas); and Harold Edward’s account of a potential grave (well, body) robbing incident involving Richthofen.

Many of these storytellers are true raconteurs. Their stories have vibrancy and immediacy. You can feel their fear on dangerous bombing missions when they know the odds of not returning. You can appreciate David Evans’ and Val Hancock’s support of past actions and policies even though they involved morally difficult circumstances. You feel for Bobby Gibbes who rose above his own lack of confidence. And you wonder how Australian political history would have changed if John Gorton had been one of the pilots of the 43 Hurricanes out of 51 destroyed over Singapore in the early days of January 1942.

Counterbalancing the drama of these stories is the humour, and this is another strength of this collection. Some of the highlights include Caldwell recalling the potential plight of the Russian about to be thrown in the midst of his Polish pilots; Lionel Rackley, lying beside a rail line after baling out from his plane and realising a train had pulled his harness off him, declaring ‘I’d had my nine lives’; and Ron Guthrie’s prison camp humour as he explains that ‘you had to be in the know as to when a chicken had been caught to get any of it because between 300 men it didn’t go very far.’ But the one that really cracked me up was Bill Simmonds’ recollection of one of his flights: ‘I radioed Moose, “Hey, do you realise where we are?” “Of course, we’re over [RAF] Celle.” “Well, how long have they been equipped with MiGs?” “Oh, my God!”’

There may have been a number of things that annoyed me about this book, but when I put it down, I found myself wanting more. Luckily, the transcripts are available from the Australian War Memorial and many of those interviewed here have penned their own recollections. As a taste of Australian experiences during twentieth century conflicts, this is worth reading. We should be grateful Ken Llewelyn recorded these interviews, thus preserving the voices and experiences of a small group of Australian aircrew.