Peter Monteath: P.O.W. Australian Prisoners of War in Hitler’s Reich

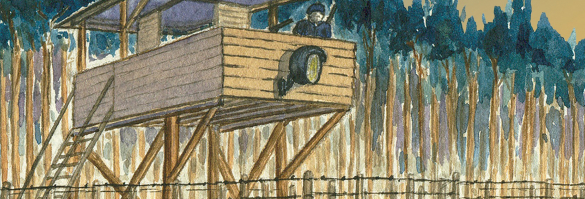

Australians from every field of conflict in the Second World War found themselves as prisoners of the Reich. A handful of merchant seamen were captured but were far outweighed in numbers by aircrew and soldiers, some of whom were captured as early as the Battle of France.

Part of the blame for this perception perhaps can be laid at the feet of Hogan’s Heroes. Repeated ad nauseum and available on video and now DVD, this popular television series has left a sad impression in popular culture that the experience of European prisoners was a laugh, a lark, and that their keepers were bumbling incompetents.

Perhaps the Australian government also shared the general belief as prisoners of the Germans were excluded from the 2001 Compensation (Japanese Internment) Bill which, on recognition of the hardship and suffering experienced, provided a one-off compensation payment to those interned as a prisoner of war by the Japanese in the Second World War. Happily, this ‘oversight’ was rectified in 2007. Interestingly, my friend Bill Rudd of the Victorian Branch of the Military Historical Society of Australia, himself a former prisoner and dedicated to researching the experiences of Australian and New Zealand prisoners who remained behind enemy lines (see his www.anzacpow.com website) tells me that, after a review in 1987 set up by Prime Minister Hawke, some Anzac European POWs—mainly airmen—received an ex-gratia payment of $10,000 for having been transferred from Geneva-supervised German prison camps to Nazi concentration camps. Up until that review, the Australian Government had steadfastly refused to recognise such transfers. I am getting off the track but it is important to note that Monteath is the first author Bill Rudd has come across that brings up the significant matter of reciprocity of Australian treatment to the German POW held in Australia, a vital point in Germany not involving itself in the ICRC Exchange of POW programs until late 1943.

The European prisoners had remarkable experiences of hardship. Perhaps if P.O.W had been published earlier, and their stories brought to a broader readership, Australian prisoners of the Reich might not have had to wait so long for their much-deserved compensation. Monteath’s deeply researched analysis of the German prisoner experience would have done much for their cause.

The first few chapters of P.O.W. give the impression that this is an intimate, personal account of the prisoner experience. Many former prisoners are introduced in quick succession—telling how they were captured—and the reader expects that at some point their stories will be taken up again and Monteath will eventually relate the ‘what happens next’. But for the majority this is not so. This is a narrative account of prisoner experiences and Monteath uses first-hand accounts to illustrate his overarching themes—Capture, Captivity, Liberation—and there is little place for detailed biography. At first flush this is disappointing as Monteath skilfully and quickly creates pen biographies so the reader is immediately engaged. However, it soon becomes apparent that Monteath has presented a detailed, competent narrative and analysis which, reflecting his academic background, makes use of official British and Commonwealth records as well as ones from German sources. He also points out the significance of the Nazi culture on the treatment of prisoners and the degradation of all enemies of the state.

Given my own interest in social military history I feel it is almost heresy to admit that in this case Monteath’s approach is more important than just telling the personal stories. And why? Because, incredibly, (as far as I can recall at least) nothing so detailed and all-encompassing on the German prisoner of war experience has been published previously in Australia: just one chapter in the official history of the air war in Europe (Herington: Air Power Over Europe) and assorted scattered accounts of various aspects of the experience. (New Zealand has been better served with an entire volume of their Second World War official history devoted to prisoners of German, Italian and Japanese forces ie Wynne Mason’s Prisoners of War.)

Peter Monteath is to be congratulated for rectifying this dearth of detailed, authoritative and analytical narratives. P.O.W. is an excellent book and will do much to bring the European prisoner experience out of the shadow to stand alongside that of the Japanese prisoners. P.O.W is readable, accessible and the analytical framework reflects sound research. This important book should become known as the official history of the Australian prisoners of the Reich.