Surviving the Great War: Australian Prisoners of War on the Western Front, 1916–18.

Surviving the Great War: Australian Prisoners of War on the Western Front, 1916–18. By Aaron Pegram. Cambridge University Press, ( Australian Army History Series), xv + 266 pp. ISBN 9781108486194 (Hardback) Published: November 2019. $59.95

Captivity is one of the most challenging of human experiences. The 3,848 Australians taken prisoner on the Western Front considered it an ordeal they had to endure. Not only did they confront this arduous test they, as Aaron Pegram demonstrates, survived it.

Prisoners of war (POWs) were less than two per cent of Australia’s Western Front battle casualties. Because of the small numbers compared to 60,000 Australian deaths, thousands of wounded, and the returned ‘shattered Anzacs’, the experiences of Australia’s Western Front POWs have been overlooked. This, as Pegram explains, is because captivity does not fit easily into the First World War’s dominant narratives. They focus on Australian martial success; the bronzed Aussie fighter of the Anzac Legend; and commemoration of wartime loss. Within these national narratives, captivity is perceived as a story of defeat. POWs are passive contradictions of the Anzac Legend’s martial masculinity. Western Front captivity also sits awkwardly alongside two Second World War tropes. The first, extrapolating from the experiences of prisoners of Japan, portrays captivity as a powerless state where POWs are emasculated, but honourable, victims of unabating trauma. The second, deriving from a European experience (erroneously) noted for daring and occasionally successful escape attempts, celebrates captivity as an exciting adventure story replete with heroic escapers.

Surviving the Great War: Australian Prisoners of War on the Western Front, 1916–18 deftly establishes a new captivity narrative. Pegram constantly relates captivity to service; Australian soldiers and airmen were captured as a consequence of battle. They may have surrendered because there was no alternative other than death, but they had immediately beforehand proven their martial agency and, in many cases, battle success. While Surviving the Great War is not an account of extreme trauma at the hands of captors and ensuing heroic victimhood, it does recognise that some POWs experienced ‘barbed-wire fever’ and conditions which were difficult and, in some cases, impossible to bear. Pegram counterbalances this with details of the Australians’ successful mitigation of hardship through their own agency and that of the Australian Red Cross Society. The personal triumph of each man’s survival has no taint of heroic victimhood or the inherent (almost condescending) pitifulness of that trope because, by attempting to manage and ameliorate challenging conditions and treatment, they exerted agency—just like those soldiers embraced by the Anzac Legend.

Surviving the Great War is the first major study of Australian captivity on the Western Front and the effects of captivity in post-war life. It draws on contemporary personal and official evidence held in Australian, British, and German repositories. Pegram privileges contemporary personal evidence rather than late-life memoirs and oral histories which may have been affected by prevailing narratives of victimhood published or created as public attention turned to the experiences of prisoners of the Japanese. Personal documents include 2,500 repatriation statements, fifty wartime diaries and near contemporary unpublished manuscripts, as well as, from German archives, captured Australian diaries and letters. These ego documents ensure a raw, unpolished immediacy of experience, response, and emotion. As well as illustrating Pegram’s argument, salient extracts explicate what happened and how the men felt about it. They remind the reader that Australian prisoners of war are human individuals, not simply data sources.

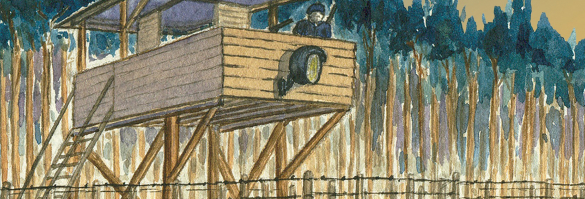

While Surviving the Great War is structured thematically, each chapter outlines significant phases of the war. The introduction positions Great War captivity within Australian historiography. Six chapters explore and analyse capture; the reciprocity principle; POWs as intelligence assets; the fortifying work of the Australian Red Cross Society and its volunteers; the myth and reality of escape; and autonomy and independence within captivity. Recognising that captivity did not end at liberation, the seventh chapter examines repatriation, homecoming, and the post-war experiences of 264 men of the 13th Battalion. Surviving the Great War includes a number of photographs, mainly from Australian War Memorial collections, as well as two useful maps which detail Western Front trench warfare and German advances in 1914 and 1918, and the main German prisoner-of-war camps. Printed on facing pages, these maps reinforce the interconnectedness of battle and capture. The narrative is also complimented by three tables: ‘Mortality of British and dominion POWs’; ‘Australian POW deaths in captivity’; and ‘Australian escapes from German captivity’. Drawing on a detailed mortality study, Surviving the Great War is supported by sound statistical analysis as well as details of individuals’ family, social, and military backgrounds.

Surviving the Great War illustrates that German treatment was not a uniform experience. While death and burial records of those who died in captivity reveal how some Australians experienced extreme violence at the hands of their captors, there was usually fair dealing by captors. Living conditions in camps varied from adequate to atrocious depending on social, economic, and military context. In highlighting the multiple facets of captivity and the disparity of personal experience, Pegram takes the middle ground. He argues that German treatment of Australian POWs was not brutal, nor was it benign. It was somewhere in between.

A key theme is masculinity. Pegram explores threats to it and personal agency in asserting it. He argues that capture was ‘a function of the dynamics of the battlefield and the ability of one military force to achieve tactical superiority over the other’. Here Pegram evinces deep knowledge of the course of Western Front action and strategy to explain that men of action did not surrender because of combat ineffectiveness, low morale, or lack of resilience during the hard slog of trench or aerial warfare. They were captured as a consequence of battle or its immediate aftermath. Yet, by surrendering, many men believed they had forsaken their manhood. By challenging that conception, Pegram demonstrates that surrender was not an entirely passive act. As the alternative may have been death, surrender, then, was an act of manly agency—the choice to be pragmatic. After capture, the Australians did as much as they could to affirm their masculinity as they endured and ultimately survived captivity. Not only had they upheld the masculine Anzac ideal in battle, they had honoured their martial imperative. Surrender may have signalled the end of one battle—trench warfare—but it also heralded the beginning of another: the battle to survive wartime incarceration. Many in captivity continued to confirm their martial agency through acts of resistance and sabotage.

Surviving the Great War highlights commodification of prisoners of war. The Geneva and Hague conventions stipulated humanitarian treatment. While they were not always adhered to, the reciprocity principle provided that each belligerent treated captives well to ensure their own nationals were in turn treated well (although, it must be recognised that Germany did not always have the resources to do this). Allied prisoners of war, then, were commodities which could ‘buy’ protection for German captives in Allied hands. POWs were also intelligence assets for Germany. Captors deliberately, almost charmingly, cajoled information from unsuspecting POWs during soft interrogation sessions. They recognised that material objects were sources of military information. Despite being forbidden to carry them into battle, the number of letters, diaries, and other documents confiscated by the Germans on capture suggests that Australians failed to appreciate the military value of their personal possessions.

Particularly noteworthy is Pegram’s dissection of the Holzminden illusion—the Great War equivalent of the Colditz myth. Only 43 Australians succeeded in escaping. As such, Pegram argues that, contrary to popular tropes formulated during the interwar years and more recently because of high profile Second World War escapes, ‘heroic escape attempts’ were not the dominant characteristic of Western Front captivity. Although those at home may have assumed their loved ones wanted to flee German confinement (as evidenced by the number of hidden escape aids confiscated from care packages), escape was not a duty; it was optional for Great War servicemen. In most cases, it just was not possible. In many ways, staying put was the most pragmatic thing to do. In remaining, the vast majority of Australian prisoners of war exerted personal agency to make the most of life in captivity. In doing so, they were agents in their own survival.

Pegram firmly positions the experiences of Australian Western Front prisoners of war within Australian and international military and captivity historiography. His sound scholarship is enhanced by deep archival work and statistical analysis. Surviving the Great War is balanced, nuanced, and well-written. While aimed at a scholarly readership, it is eminently accessible to the general reader. In his conclusion, Pegram states that ‘No single Australian narrative emerged from captivity on the Western Front’. Surviving the Great War now establishes a clear narrative of achievement: prisoners of war found ways to overcome the challenges of captivity and regarded their survival as a personal triumph. By highlighting individual stories, Pegram never forgets the Australians’ essential humanity. I have no hesitation in recommending this exceptional examination of POW life. Surviving the Great War is an important work which illuminates captivity and its legacy.

An edited version of this originally appeared on the Honest History website. http://honesthistory.net.au/wp/alexander-kristen-they-also-served-australians-dealing-with-the-challenge-of-captivity-during-the-great-war/